The New Jersey Department of Transportation Bureau of Research convened a Lunchtime Tech Talk! Webinar on What Happens Now? Virtual Public Involvement During and Beyond COVID-19 on October 6, 2021. Amanda Gendek, Manager of the NJDOT Bureau of Research, welcomed everyone to the event which included presentations by five representatives of public sector transportation agencies who discussed the immediate transition and ongoing adaptation to virtual platforms to engage with the public for transportation plans, projects, and other activities, and the benefits and challenges associated with this shift. Of particular emphasis was outreach to underserved and vulnerable populations.

Facilitators for the Tech Talk, Andrea Lubin and Trish Sanchez, from the Rutgers University-Voorhees Transportation Center, Public Outreach and Engagement Team (POET), opened the session with reference to their work on NCHRP Synthesis 538: Practices for Online Public Involvement, and the next phase of work, NCHRP 08-142 Virtual Public Involvement (VPI) – A Manual for Effective, Equitable, and Efficient Practices for Transportation Agencies. During the pandemic, Rutgers POET has conducted public engagement which transitioned to virtual for the South Jersey Transportation Planning Organization, Somerset County, and Middlesex County’s Destination 2040 projects. Ms. Sanchez noted the need to experiment with different engagement practices to find what works for each community, and the benefits of building partnerships with local organizations to reach a broad audience. She also noted challenges with VPI such as the digital divide, internet access, and staffing. Ms. Lubin discussed a 2020 study conducted for the Kessler Foundation and interviews with social service agencies and community organizations that offered lessons learned when conducting virtual outreach with vulnerable populations. Despite challenges, Ms. Lubin emphasized that VPI has expanded engagement opportunities in many instances to those who had previously been unable to participate in-person due to obstacles including transportation and childcare.

Rickie Clark, Transportation Specialist with FHWA, noted that Virtual Public Involvement (VPI) is one of the innovative initiatives supported in the fifth and sixth rounds of the agency’s Every Day Counts Initiative. He reviewed the legislation and regulations that requires early and continuous public involvement in the transportation planning and project development process. To meet those requirements during the COVID-19 pandemic, FHWA issued VPI Temporary Guidance that will remain in effect until the pandemic has ended. Mr. Clark encouraged the use of a wide array of VPI tools that can be customized to the needs of particular projects and audiences. VPI extends outreach to the public and enables the public to engage with transportation officials efficiently and effectively. For those who have limited access to the internet, he emphasized that transportation agencies must provide alternatives to ensure full, fair, and meaningful participation for all. Mr. Clark noted that New Jersey is using many VPI innovations.

Jamille Robbins, Public Involvement, Community Studies & Visualization Group, Leader, North Carolina DOT, spoke on how his agency has reached underserved communities with VPI. He discussed the importance of pursuing thoughtful marketing to support the success of VPI and other outreach efforts designed to educate and inform the public and other stakeholders in the transportation project development process. He explained that broadening outreach and increasing engagement contributes to transparency and builds trust. He noted that social media is an effective tool for reaching rural, lower-income, Black, Hispanic, and less-educated populations, and that mobile phone friendly communication is essential. However, agencies should not be solely relying upon VPI. Traditional media, webpages, partner agency and organization networks, newsletters, postcards, door hangers and local access television and radio remain effective tools for reaching traditionally underrepresented groups. Similarly, integrating the use of phones to collect public comments can augment traditional methods for collecting input, such as paper surveys. Mr. Robbins shared experiences with utilizing a variety of VPI tools and platforms including public engagement software such as publicinput.com and the social networking service Nextdoor. He also described pre-recorded project information videos as a highly effective tool for controlling messaging and highlighted the agency’s use of online engagement platforms for live meetings, with the recordings placed on the web, so that constituents can access them and provide feedback at any time. Mr. Robbins also promoted the use of project visualizations, including 3D renderings and interactive animation that can be easily dispersed across online communication channels and improve understanding of proposed projects. While sharing many tools creatively being used by NCDOT, Mr. Robbins balanced his remarks with several takeaways and lessons learned observations about the limitations of VPI for reaching underrepresented communities.

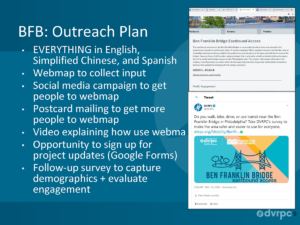

Alison Hastings, Associate Director, Communications, Delaware Valley Regional Plan Commission (DVRPC) spoke about the agency’s use of VPI in the Long Range Plan 2050 Visioning process, and for the Ben Franklin Bridge Eastbound Access project, and the regional MPO’s anticipated integration of VPI for public involvement in the post-pandemic era. When pivoting from in-person public engagement to virtual events, Ms. Hastings listed several themes that required consideration: accessibility and accommodations, recreating the in-person experience, setting ground rules and ensuring security. She also described her team’s considerations in determining the specific staffing roles needed for their virtual events, such as lead facilitator, technical assistance leader, and comment response facilitator, among other roles. She noted identifying these positions has helped to ensure smoother virtual events.

DVRPC has used many VPI platforms and tools, both old and new, such as videos, targeted social media campaigns, live transcription and captioning in meetings, web maps, and postcard mailings and noted that public participation has increased with their VPI efforts. Ms. Hastings discussed the advantages of meeting platforms that run well on browsers and smart phones and enable participation in underserved communities that lack internet access. In the future, DVRPC’s equity checklist will include using American Community Survey data to understand the demographics of the project area, communicating why the meeting is important, using Google forms to build contact lists, preparing the team for the challenges of online meetings, experimenting with different outreach, and evaluating the VPI process. She anticipates that hybrid meetings – in person and virtual – will continue and may require additional staff to run efficiently to achieve desired outcomes.

Vanessa Holman, Deputy Chief of Staff and Megan Fackler, Director of Government and Community Relations at NJDOT explained that their Public Information Centers (PICs) and other outreach must be compliant with Title VI requirements. Due to the pandemic, they needed to find ways to bridge the digital divide which is economic, generational, and geographic. NJDOT has combined established methods of engagement with virtual methods, and in particular, collaborated with stakeholders through social media, websites, and digital news sources. They noted that virtual meetings have helped to remove some barriers to participation, such as the need for transportation and childcare. Ms. Holman shared that they have lost some of the interaction typical of an in-person meeting, and noted the different staff demands of online meetings such as prepared scripts. The Department has also expanded communication in other ways, including through 1-2 page project update memos, written in plain language, for public officials. They now tend to over-communicate and continue to use a range of tools. These efforts are resulting in more public participation and comment in general.

Public involvement tools are available to engage underserved and vulnerable populations and expand outreach so every community member can participate in transportation decision making. Click for Andrea Lubin and Trish Sanchez's presentation

Mr. Clark noted that there is no one-size-fits-all public involvement process and promoted the use of an array of public involvement tools to communicate with the public and receive input. Click for Rickie Clark's presentation

North Carolina DOT uses 3D visualizations and interactive animation, among other tools, to help public involvement participants understand proposed projects and impacts. Click for Jamille Robbins' presentation

DVRPC used both old and new methods of communication for the Ben Franklin Bridge Outreach Plan. Click for Alison Hastings' presentation

NJDOT was successful with their two-week, on-line PIC for the Rt. 80 and Rt. 15 Interchange project. They received large volumes of survey responses and discovered key times for public participation that will inform future efforts. Click for Vanessa Holman and Megan Fackler's presentation

At the end of the event, the speakers responded to questions posed by attendees through the platform’s chat feature.

Q. How expensive is NextDoor?

Jamille Robbins: I don’t believe there’s a huge cost associated but I would have to check with our social media coordinator.

Q. What program did North Carolina use to do 3D presentations?

Jamille Robbins: We use 3D Studio Max for a lot of the presentations.

Q. How do you provide for two-way communications and conversations in an online environment that would occur at in-person events?

Alison Hastings: The platforms, such as Zoom, help. The chat box becomes a primary source of input since you can save it. Conversations can happen in breakout rooms with small groups and a facilitator sharing a screen while using Google docs to record notes. Platforms push updates that provide these tools to emulate the in-person experience.

Trish Sanchez: Break-out groups allow people to feel more comfortable speaking openly.

Andrea Lubin: Especially if they are intimidated by large groups.

Q. What are typical costs for publicinput.com?

Jamille Robbins: North Carolina uses it on all projects and it is cost-effective, but I do not know specific costs.

Q. For NJDOT: Have you received feedback, either positive or negative, on the VPI process or the platforms used and has that encouraged you to change anything in your VPI strategies?

Megan Fackler: Not thus far. We have received questions on the platform, and requests for technical assistance. It is important to provide a phone number for people to reach out prior to a meeting if they are having difficulties accessing the meeting.

Q. For Rickie Clark: If a municipality requested an in-person event, would FHWA provide guidelines for conducting such a meeting?

Rickie Clark: The possibility for in-person meetings would depend on state and municipal guidance for in-person engagement, as well as the guidance of local health officials. During the pandemic, the VPI Temporary Guidance is in effect.

Q. If you could offer one piece of advice for VPI for underserved or vulnerable populations, what would it be?

Andrea Lubin: What I heard from Jamille was the power of radio advertising to target outreach, based on the number of people who are regular radio listeners.

Rickie Clark: From the federal perspective, agencies must have a public involvement plan in place to begin with. Agencies should evaluate the effectiveness of VPI tools. DOTs have become more nimble in modifying their approach. Imagine a time after COVID-19 when a hybrid model can be used and start planning now. It will be a win-win.

Jamille Robbins: Look at the demographics of the area and population characteristics. If there are EJ or LEP communities, reach out to the local planning office or someone familiar with the area. This is the most effective way to get into those communities.

Q. How do you handle data protection in the VPI process?

Alison Hastings: Don’t ask the question if you can’t protect the information you gather. Also, sunset dates determine how long a survey remains open. Set a date for expunging contact information after gathering that information. Use the same process for focus groups.

Jamille Robbins: We are simplifying the demographic information we are requesting. Asking for a name, email, and address may pass a threshold. Keep in mind that information gathered at a public meeting is a matter of public record.

A recording of the webinar is available here.