A team of researchers from New Jersey Institute of Technology have improved upon methods to identify high risk bridges in New Jersey to facilitate prioritization for repair or replacement. They have accomplished this through validating and advancing a new multi-dimensional model to analyze bridge scour and make appropriate recommendations. Bridge scour is the gradual removal of sediment around bridge abutments or piers caused by water movement, which can affect the long-term integrity of a bridge structure. By collaborating with three New Jersey consulting firms, the researchers hope to transfer their findings for statewide application.

Read a short technical brief summarizing the project background and findings (November 2017)

The researchers developed a “Scour Evaluation Model” or SEM that reflects New Jersey’s unique geological and hydrologic/hydraulic conditions while taking a more comprehensive approach than previous practices. NJDOT joins a number of other state DOTs that use a modified method for scour evaluation, as standard methods have often yielded conservative values for scour depth, or yielded disparities between predicted and observed scour.

SEM uses seven parameters to evaluate scour risk. One key parameter is the use of envelope curves, which “correlates the upper range of expected scour depth with a measurable hydraulic variable such as embankment length or pier width.” It was originally developed by USGS and original curves were based on bridge studies in 14 states. Many of the bridges were located in South Carolina’s Coastal Plain, which has a similar geology to New Jersey.

Another key parameter is determining whether a bridge has experienced a 100 year storm, and if so, how it performed. The other five include erosion resistance of streambed, bridge age, field scour observations, channel stability, and HEC-1800 scour calculations.

In their report, the team summarized the impacts of their SEM application. The bridges were rated by priority levels (1-4) based on the analysis. First, 17 bridges were evaluated using an abbreviated SEM procedure to prescreen high risk bridges. These 17 bridges were determined to be Priority 1 (high risk) or Priority 2 (medium-high risk) and in need of repair or replacement.

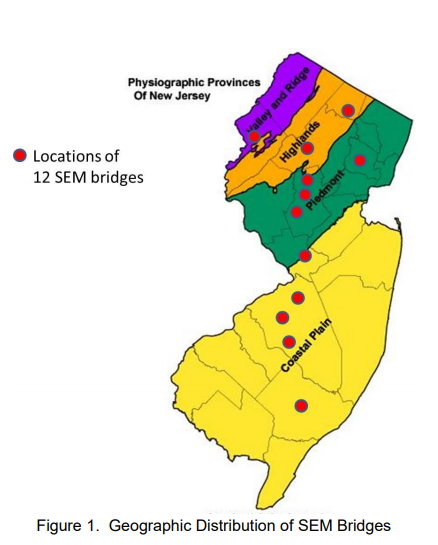

Secondly, the project evaluated 12 bridges fully using SEM with the participation of three consulting firms. Two of the bridges in the study were found to be Priority 1 (high risk), one bridge was found to be Priority 3 (medium to low risk) and nine bridges were found to be Priority 4 (low risk). The low risk bridges were then recommended for removal from the scour critical list.

Secondly, the project evaluated 12 bridges fully using SEM with the participation of three consulting firms. Two of the bridges in the study were found to be Priority 1 (high risk), one bridge was found to be Priority 3 (medium to low risk) and nine bridges were found to be Priority 4 (low risk). The low risk bridges were then recommended for removal from the scour critical list.

Third, the research study was able to validate the use of “envelope curves” to evaluate scour at 15 bridges across 9 New Jersey counties with a range of characteristics and flooding histories.

The team’s goal was to accelerate the transfer of the model into statewide practice, so that it can be fully applied to New Jersey’s inventory of scour critical bridges. This was accomplished through meetings, conference calls and field visits with participating consultants.

The team’s full research and implementation process can be read in the following report:

SCOUR Evaluation Model Implementation Phase

View the team’s presentation slides from the 19th Annual NJDOT Research Showcase