Jan 3, 2025 | Innovation Interview, Innovation Spotlight, News, Research Project, Research Showcase, Research Spotlight

Traffic safety and mobility, two critical areas in transportation engineering, both require the collection and analysis of large data sets to produce proactive and comprehensive solutions. Transportation engineers have started to increasingly focus on using innovative...

Jun 12, 2020 | News, NJ STIC, Research Project

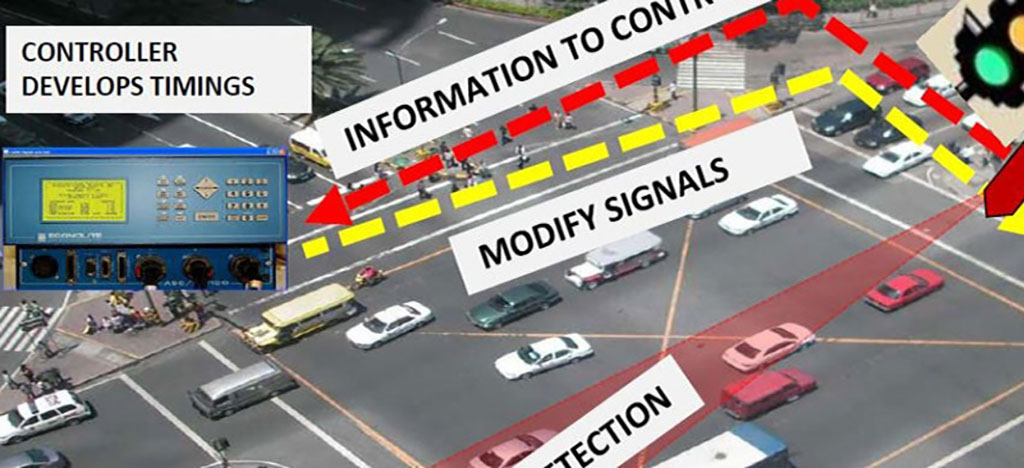

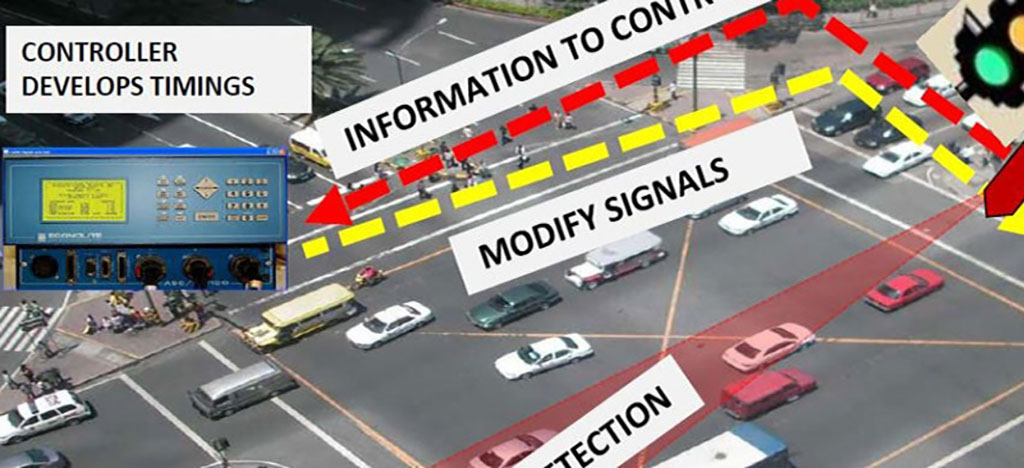

Adaptive Signal Control Technology (ASCT) is a smart traffic signal technology that adjusts timing of traffic signals to accommodate changing traffic patterns and reduce congestion. NJDOT recently deployed this technology in select corridors and required a set of...

Dec 12, 2019 | News, NJ STIC

As technology advances, so does the need for data—information that allows engineers, planners, and others to utilize innovative ways to improve transportation and safety. To implement smart traffic systems, whereby centrally controlled traffic signals and sensors...

Jan 29, 2018 | Lunchtime Tech Talk!

NJDOT Assistant Commissioner for Transportation Systems Management, C. William Kingsland, spoke about Adaptive Signal Control (ASCT) during the third Lunchtime Tech Talk hosted by the Bureau of Research on November 29, 2017. The Federal Highway Administration (FHWA)...