The interstate highway transportation building program undoubtedly yielded significant mobility and economic benefits for the nation in the post WW-II era but also imposed environmental and public health burdens for less favored communities. The benefits and burdens of the building program were not equitably distributed; the burdens were often disproportionately borne by predominantly minority and ethnic populations and lower-income communities that were powerless to halt transportation and land use decisions made in the name of “progress”, regional mobility, more efficient auto and truck travel, and urban renewal.

The Reconnecting Communities Pilot Program, a new and innovative program in the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law, takes a small step toward repairing and redressing the adverse consequences of these past planning and engineering decisions. (1)

The Bipartisan Infrastructure Law (BIL) enacted in the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act has been described as a “once in a generation” investment in our nation's infrastructure, promising two million jobs per year and delivering needed financial assistance to transit, highways, water, power, and communications. While much of the BIL’s transportation funding is intended to encourage and prioritize the repair, reconstruction, replacement, and maintenance of existing transportation infrastructure, the BIL also tilts investment and resources for programs, new and old, to tackle the challenges of the 21st century in the realms of safety, equity, and climate change and resilience.

The BIL includes an innovative new program, the Reconnecting Communities Pilot Program, that sets aside $1 billion to “restore community connectivity by removing, retrofitting, or mitigating highways or other transportation facilities that create barriers to community connectivity, including, mobility, access, or economic development.” From 2022 through 2026, the pilot program will receive $500 million from the Highway Trust Fund and $500 million from the general fund for Planning and Capital Construction grants. (2)

The USDOT explains that the Reconnecting Communities pilot program will help reconnect communities that were previously cut off from economic opportunities by transportation infrastructure. Reconnecting a community could mean adapting existing infrastructure– such as building a pedestrian walkway over or under an existing highway– to better connect neighborhoods to opportunities or improve access through crosswalks and redesigned intersections. The FY22 Notice of Funding Opportunity (NOFO) has been issued and is available on the USDOT website.

The primary goal of the program is to reconnect communities harmed by transportation infrastructure, through community-supported planning activities and capital construction projects that are championed by those communities. The planning grants support the funding of the planning processes for the entity performing the reconnection, to include project design and public outreach to the historically disconnected communities. Outreach can be tailored to overcome mistrust of the government entity that sited the infrastructure that disconnected the community, and explore potential strategies to redress the burdens of these past siting decisions. After planning is complete, capital construction grants will fund work to remove, replace, or mitigate the facility. The federal government will fund up to half of the costs of these projects.

What the Reconnecting Communities Program Recognizes

The program is noteworthy for its recognition that, historically, many public and private entities presided over land use policies and the siting of transportation infrastructure that resulted in the isolation and segregation of poor and marginalized populations from the broader community. Some scholars have traced causes of spatial segregation to unfair enactment of zoning laws in the 1930s that peddled "health and safety" as the rationale for carrying out discriminatory land use policies. Over time, the color line boundaries were maintained through redlining, realtor steering, block-busting, and disinvestment that shaped a geography of unequal access to opportunities for those concentrated in disadvantaged communities.

The intent of early zoning was to reinforce protection of citizens’ health and safety as established in nuisance law. It gave governments police powers to make sure that the state and its cities could be proactive in anticipation of negative impacts. Unfortunately, with these powers, the enfranchised voter, politician, planner, and engineer set the parameters of health and safety to fit their preferences and biases. Governments could consolidate disenfranchised populations in specific areas and permit the siting of health and safety nuisances in these communities through “spot zoning”. For example, in South Central LA, a majority black neighborhood, the City began to spot zone industrial uses in commercial portions of the neighborhood. An electroplating plant in the area exploded in 1947 killing 5 local residents and 15 workers while damaging 100 homes. The property next to a church was spot zoned industrial and when the pastor raised their concerns, they were why “Why don’t you people buy a church somewhere else?” (3 pp. 55-56). These local decisions had the silent approval of state and federal governments.

Concurrently, the rise of the personal automobile required the allocation of space to make trips easier and faster in and through traditionally dense American cities. At the beginning of the Highwaymen Era, cities sought to build expressways and parkways, often ignoring the residents who sat in the bulldozer’s path. The Cross-Bronx Expressway is an often-referenced example of how damaging the siting of urban expressway projects were to community life and how powerless the affected communities were to halt siting decisions. In 1945, Robert Moses, perhaps the most infamous highwayman, sought to construct a seven-mile trench highway through the Bronx. He looked at the stretch as his to shape. Even when offered alternatives to his vision, alternatives that would have resulted in preserving more of the neighborhood and homes, he persisted with his alignment through the Bronx and its displacements of the families along the way. (4 pp. 839-878) Moses was not alone among the planners and engineers in ignoring the preferences and plight of local residents.

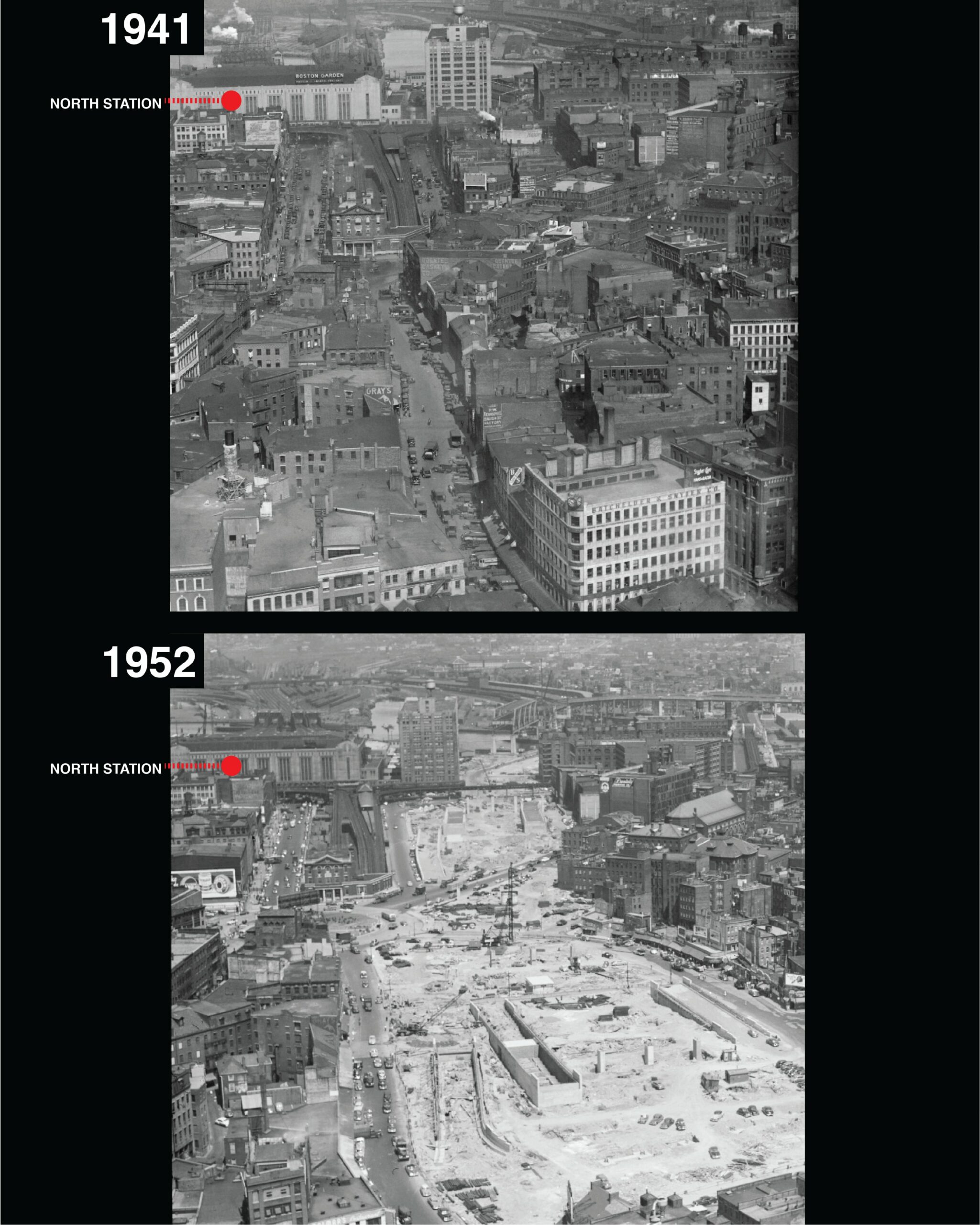

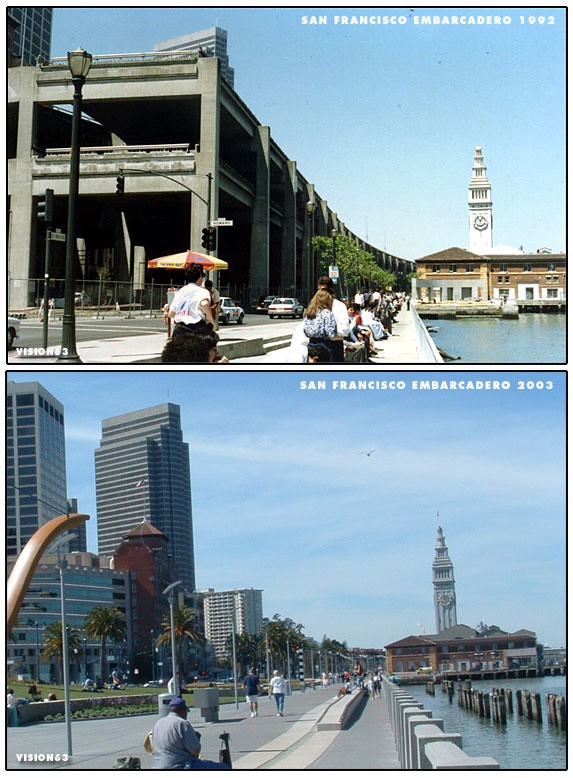

This process accelerated with passage of the Federal-Aid Highway Act in 1956 that funded the construction of mostly free to access, grade-separated roads that linked cities, towns, and states. The money and power prescribed to states from the federal government allowed the powers that be to run highways through neighborhoods of primarily underrepresented populations. The Embarcadero Freeway in San Francisco (5 pp. 46-96), I-93 in Boston (6), the several I-80’s of Oakland (7) , and many more cut deep into their cities in the name of progress (3 pp. 127-129). Individuals saw the divisive impacts of these highways on communities and eventually rallied in several cities to prevent their expansion, but it was too late for many communities. Hulking multilane highways that produced noise and air pollution cut up and cut off neighbors and communities (5 pp. 94-121).

Over time, people have organized and sought to mitigate or reverse the impacts of these highway sitings on the urban landscape. Several governmental bodies are engaged in planning processes for community reconnection and several projects have been successfully completed in the past two decades. The most famous two examples are The Embarcadero in San Francisco and Boston’s Big Dig. The Embarcadero Freeway was a multilevel highway that separated San Francisco Bay from the City. In 1989, an earthquake struck the Bay Area. The Embarcadero crumbled with the quake and people began to ask questions about how this massive waterfront space could be used. After fights with the State and a 6-5 vote at the municipal level, a boulevard and trolley tracks replaced the Embarcadero. (8) For the first time in decades, the bay, not pillars and concrete, bound San Francisco at its north end.

The most famous reconnection on the East Coast is probably the Big Dig. When constructed, I-93 tore through the historically Italian North End, cutting it off from the City proper. With no transit facilities, the neighborhood was isolated with large spans casting shadows into the residences of the North End. While the North End could not be saved, witnessing the damage caused by the highway sparked highway revolts throughout the Boston area leading to the cancellation of several highway projects in Boston. With traffic pressures rising and lack of political will for more throughput, Massachusetts started to plan the Big Dig in the early 1980s to repair the damage done and improve throughput on I-93. Over the next 35 years, Boston engaged with the North End community, the citizens of the City and business and waterfront interests to shape the public space that would follow. This development process resulted in the current boulevard and park that caps I-93. (6)

Recent and Promising Reconnections

In Boston and San Francisco, the removal of the highways revived the space, but also led to land speculation that has fueled displacement and gentrification. With the successes and mistakes of these community reconnections in mind, other states and cities are exploring restorative strategies that will avoid and minimize community displacements.

The Inner Loop of Rochester is one of the more recent reconnection projects on the East Coast. Its transformative effects have served as a "demonstration project for highway removal in other parts of the city" (9). When completed in 1965, I-490 and New York State Route 940T created a loop around Rochester’s downtown, making the area difficult to access for most residents. As the 1970s brought significant economic impacts to Upstate New York, Rochester’s population declined and the city recognized the need to reconnect the downtown with the rest of the city. In the early 2000s, several proposals slowly coalesced into public engagement in 2013 through which the citizens helped shape plans for the initial removal of the loop. For $21 million, Rochester removed and buried its below grade highway and have since replaced it with housing and mixed-use development. (9,10)

Built between 1956 and 1968, I-94 connected the Twin Cities, but in the process badly damaged the majority Black neighborhood of Rondo, displacing 60 percent of its residents. In the late 2000s, a freeway cap was proposed to cover the highway in portions, but like many proposals at the time, it languished due to tight public budgets. In 2021, a local nonprofit, Reconnect Rondo, began spearheading an effort to reconnect portions of the community via a four-block land bridge. A land bridge option was settled on rather than removal or downgrading to a boulevard because that stretch of I-94 is considered the busiest segment of highway in the state. Reconnect Rondo is seeking justice in other ways for the cumulative impacts unleashed in part by the highway’s bisection of the community. They want to expand the neighborhood community land trust and provide housing and invest in local businesses while they pursue the highway cap. (11)

Syracuse is replacing I-81, the viaduct that runs through the core of its city. I-81’s construction ran through a neighborhood that was not only majority black, but also held a majority of all the black residents in Syracuse. The press depicted the neighborhood as slums and the State targeted the neighborhood for urban renewal in 1957. The completion of the viaduct left a soaring piece of infrastructure that isolated the community. Syracuse joined with several other municipalities in seeking to right the wrong created by I-81 and recently received funding from the State of New York to replace the highway with a boulevard. Community members fear that the growth resulting from the return of I-81 to the city’s grid may displace residents. NYSDOT’s only noted plan for addressing this potential impact is to ensure the ongoing update to the city’s development plan includes gathering the community’s input on how the new space incorporates with the community. (12-15)

New Jersey now has an opportunity to learn from those who have already planned and implemented community reconnection projects. In recent years, two highway segments have been identified as candidate projects. In Northern New Jersey, I-280, when constructed, cut a deep swath underneath the streets of Newark, East Orange and Orange. Today, the interstate segment divides neighborhoods and generates traffic, noise, and air pollution and presents unsafe pathways for pedestrians and cyclists. The North Jersey Transportation Planning Authority (NJTPA), in association with Essex County and the affected municipalities, examined strategies for reconnection in the Essex County Freeway Drive and Station Area: Safety and Public Realm Study in 2017. This study examined access and circulation issues in Orange and East Orange, and around the East Orange, Brick Church and Orange train stations, Route 280, Freeway Drive East and West, and the NJ TRANSIT elevated rail line (16). The Regional Planning Association’s Fourth Plan, completed in 2019, calls for capping I-280 in Newark and East Orange "to restore the street grid and knit back together neighborhoods." (17)

In the State Capitol, the city, county, and state all have sought to transform State Route 29. While not a part of the Interstate System, NJ-29 connects with I-195 and I-295 south of Trenton and winds along the Delaware River, separating Trenton residents from the waterfront. In 2009, the City of Trenton signed a memorandum of understanding with several agencies that proposed transformation of NJ-29 into a boulevard, but like I-94, the project has not advanced. A 2016 grant from the Delaware Valley Regional Planning Commission (DVRPC) spurred renewed interest in continuing the process. (18) With the availability of funding, advocates are seeking state support to plan and rebuild a section of Route 29 in downtown Trenton (19,20).

Can affected communities and stakeholders in New Jersey draw inspiration from the reconciliation and restoration efforts of other states and regions? With federal funding available, advocates see an opportune time to get these or other projects off the ground that could reconnect the communities once divided by past roadway siting and design decisions.

RESOURCES

- Wilson, Kea. Four Things Advocates Need to Know About the ‘Reconnecting Communities’ Program. Street Blog USA. [Online] 30 June 2022. https://usa.streetsblog.org/2022/06/30/four-things-advocates-need-to-know-about-the-reconnecting-communities-program/.

- U.S. Department of Transportation. Reconnecting Communities Pilot Program – Planning Grants and Capital Construction Grants. [Online] https://www.transportation.gov/grants/reconnecting-communities.

- Rothstein, Richard. The Color of Law: A Forgotten History of How Our Government Segregated America. s.l.: Liverwright Publishing, 2017.

- Caro, Robert. The Power Broker: Robert Moses and the Fall of New York. s.l.: Random House, 2015.

- Kelley, Albert Benjamin. The Pavers and the Paved: The Real Costs of America's Highway Program. s.l.: D.W. Brown, 1971.

- Crockett, Karilyn. People Before Highways: Boston Activists, Urban Planners, and a New Movement for City Making. s.l.: University of Massachusetts Press, 2018.

- Self, Robert O. American Babylon: Race and the Struggle for Postwar Oakland. s.l.: Princeton University Press, 2005.

- Rubin, Jasper. The Embarcadero Reborn. Found SF. [Online] u.d. https://www.foundsf.org/index.php?title=The_Embarcadero_Reborn.

- Congress for New Urbanism. Rochester | Inner Loop North. Campaign Cities. [Online] u.d. https://www.cnu.org/highways-boulevards/campaign-cities/buffalo-inner-loop-north.

- Inner Loop East - Public Participation. Inner Loop East - From Barrier to Beautiful. [Online] u.d. https://www.cityofrochester.gov/article.aspx?id=8589950580.

- Wilson, Kea. Land Bridge Seeks to Restore Minnesota Black Neighborhood. Streetsblog USA. [Online] 19 February 2021. https://usa.streetsblog.org/2021/02/19/land-bridge-seeks-to-restore-minnesota-black-neighborhood/.

- I-81 Viaduct Project: Community Grid. New York State Department of Transportation. [Online] https://webapps.dot.ny.gov/i-81-viaduct-project.

- Walker, Alissa. About Time: Syracuse’s I-81 Is Finally Being Demolished. Curbed. [Online] 26 January 2022. https://www.curbed.com/2022/01/hochul-syracuse-highway-removal-i-81.html.

- The Highway Was Supposed to Save This City. Can Tearing It Down Fix the Sins of the Past? Jalopnik. [Online] 5 April 2022. https://jalopnik.com/the-highway-was-supposed-to-save-this-city-can-tearing-1836529628.

- Congress for New Urbanism. Syracuse | I-81. Campaign Cities: Highways to Boulevards. [Online] u.d. https://www.cnu.org/highways-boulevards/campaign-cities/syracuse.

- North Jersey Transportation Planning Association (NJTPA). Freeway Drive and Station Area: Safety and Public Realm Study. 2017. Freeway-Drive-Report-Report-only-20170724.pdf (njtpa.org)

- Regional Plan Association. Fourth Regional Plan: Remove, Bury, or Deck Over Highways that Blight Communities. [Online] http://fourthplan.org/action/remove-highways.

- Congress for New Urbanism. Trenton | Route 29. Campaign Cities: Highways to Boulevards. [Online] https://www.cnu.org/highways-boulevards/campaign-cities/trenton-route-29.

- Hurdle, Jon. Push on to Jumpstart Route 29 Makeover in Trenton. NJ Spotlight News. [Online] 21 July 21, 2022. https://www.njspotlightnews.org/2022/07/route-29-highway-makeover-trenton-federal-funding-advocates-city-link-river-economic-development-civic-pride/

- Route 29 Sign-On Letter to Office of Governor. Route 29 Boulevard: Transformational Opportunity for the City of Trenton. Letter. [Online] 2 June, 2022. https://www.njspotlightnews.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/123/2022/07/Route-29-Sign-On-Letter-June-2022.pdf