According to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), transportation accounts for 29 percent of total greenhouse gas emissions (GHG) annually in the United States. To address climate change, state departments of transportation (DOTs) will need to innovate to help meet emissions reduction goals. Some agencies across the country are leading the way through the development of prevention and mitigation strategies to establish a more resilient and sustainable transportation system.

This article, the first in a two-part series, will highlight select innovations in transportation technology being deployed to reduce GHG emissions. The second, focusing on the broad topic of resiliency, will detail how state DOTs are redesigning transportation infrastructure to protect the health and safety of travelers and affected communities in the face of climate change impacts.

While by no means exhaustive, this brief scan of state actions and current research highlights noteworthy current practices and innovations to prevent and mitigate climate change impacts as well as shares examples of new and emerging emissions reduction methods being studied and deployed.

Table 1. An Overview of State DOT GHG Reduction Practices

| State | Theme | Action |

| Colorado | Active Transportation | Safer Main Street and Revitalizing Main Streets |

| Oregon | Demand Management | Mileage-Based User Fees (Limiting Demand) |

| California | Demand Management | Congestion Corridors Program (CCP). Multimodal options along corridor |

| California | Demand Management | Roadway Pricing, such as managed lanes |

| California | Demand Management | Mitigation Banks. "Cap and Trade" style bank for VMT |

| Colorado | Demand Management | Flexible Work Arrangement Policy Directive — 2 -3 day WFH |

| Maryland | Efficiency | TSMO Integrated Corridor Management. (Higher Throughput) |

| Massachusetts | Energy | Solar facilities on MassDOT property |

| California | Energy | Solar facilities |

| New Mexico | EVs | EV infrastructure implementation |

| California | EVs | Fleet conversion |

| Colorado | EVs | Expanding charging infrastructure |

| Colorado | EVs | Electrifying transit fleets through VW funds |

| Colorado | EVs | Fleet conversion — VW funds |

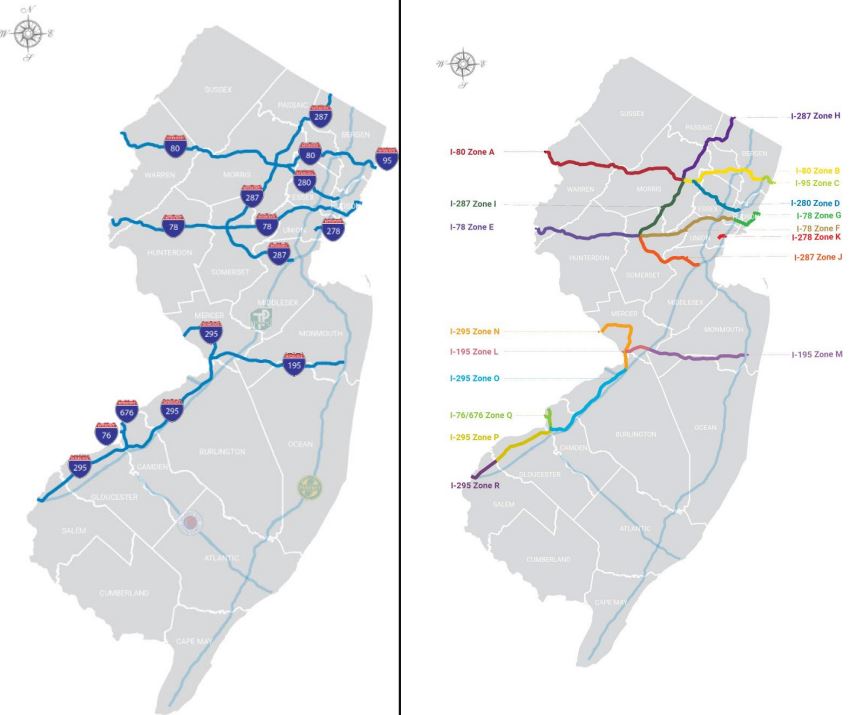

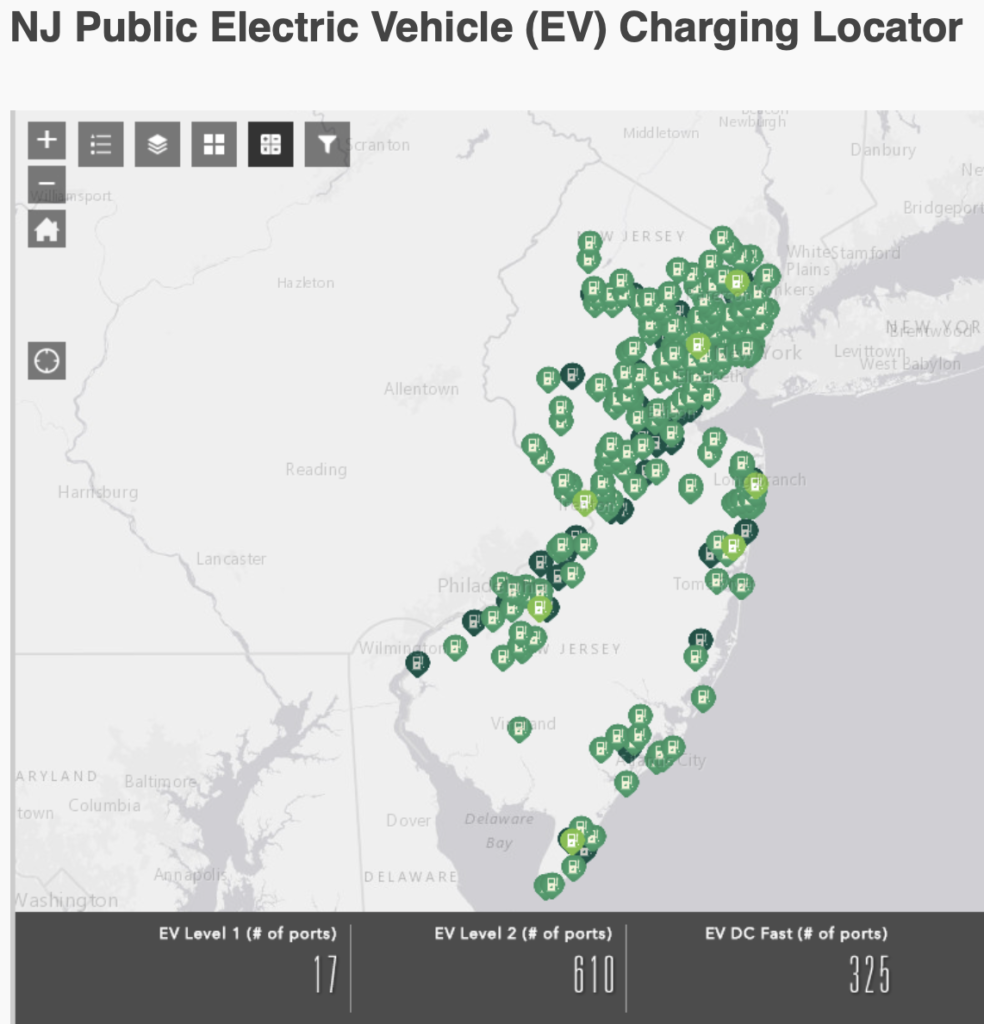

| New Jersey | EVs | Statewide Charging Infrastructure Mapping |

| New Jersey | EVs | Transit electrification |

| New Jersey | EVs | NJDOT Fleet Conversion |

| Colorado | EVs | Clean Trucking MOU-30% ZEV by 2030 |

| Maryland | Land Use | Encouraging Transit-Oriented Development |

| Colorado | Land Use | Promote land use changes along state highway |

| California | Materials | Warm Mix Asphalt (WMA) instead of Hot Mix Asphalt (HMA) |

| California | Materials | Cold in Place Recycling (CiR) |

| New Jersey | Materials | CAIT Pavement Recycling |

| Nationwide | Materials | Stiffer roadways to cut emissions and increase fuel economy |

| Oregon | Planning | Emissions considered in planning process. |

| Colorado | Planning | Add GHG emissions to decision making, and treat similarly to the existing criteria air pollutants |

| Colorado | Planning | Activity-Based Mode (ABM) considers land use, better model GHG emissions |

| Florida | Transit | Bus On Shoulder. (Mode shifting) |

| Rhode Island | Transit | Autonomous Electric Shuttle |

| Colorado | Transit | Interregional Express Bus Service — transit emissions dashboard |

Innovative Practices for Reducing GHGs

GHG reduction strategies are being instituted throughout the transportation sector, demonstrating how highway, transit and other agencies can contribute to reducing the overall carbon footprint. This article will highlight examples of technological and operational innovations being instituted by state DOTs. These efforts can be broadly assigned to four categories: Materials, Energy, Electric Vehicles (EVs), and Vehicle Miles Traveled (VMT) Reduction.

Materials

The prospect of reducing the nation’s greenhouse gas emissions from transportation seems daunting, but examples in research and practice offer several noteworthy strategies in use in this endeavor. Pavement mixtures and materials, for example, provide a promising area for research and implementation in both California and New Jersey for making their processes greener.

In California, a report found that strategic application of pavement treatments across the state’s highway network could reduce greenhouse gas emissions by between .57 and .82 million metric tons of carbon dioxide (MMT). A switch to Warm Mix Asphalt (WMA) from Hot Mix Asphalt (HMA) could reduce fuel and asphalt binder use emissions by 44 percent. Additionally, using cold in-place recycling (CiR) for repaving could reduce emissions by 52 percent.

Warm Mix Asphalt is promoted by FHWA as a greener paving alternative. Source: FHWA

In New Jersey, the Pavement Support Program (PSP), a partnership between NJDOT and Rutgers-CAIT, is currently researching pavement material recycling. Led by Dr. Thomas Bennert, researchers are testing and developing various methods for making paving materials more efficient, including studying the efficacy of recycling both pavement and pavement materials, such as disused asphalt shingles.

While such changes could seem minor, in aggregate, new materials and engineering methods could make a considerable difference. The 2020 article Potential Contribution of Deflection-Induced Fuel Consumption to U.S. Greenhouse Gas Emissions, published in the Transportation Research Record, explains how altering the composition of pavement could increase the operational efficiency of vehicles, lowering their overall emissions. According to the authors, increasing the elastic modulus of the entire U.S. pavement network could offset 0.5 percent of GHG emissions in the entire transportation sector.

Pavement is just one example of how the material aspects of roadway construction and operation can be leveraged to become more efficient and sustainable. There remain many opportunities in the materials sector for research and innovation, to build greener transportation corridors.

Energy

Highway departments—with a host of lighting, signage, and operational energy needs from administrative centers to vehicle fleets—have the potential to alter how their systems are powered. Already, Massachusetts and California provide examples of how highway departments can invest in greener energy usage.

The Massachusetts Department of Transportation (MassDOT), through its Highway Renewable Energy Program, has installed photovoltaic (PV) systems, more commonly known as solar panels, at five sites along its highway network.

Through a public private partnership, MassDOT leases land to a private company, which constructs and operates the renewable energy facility, in this case PV systems. The private company is able to take advantage of federal and state incentives, allowing MassDOT to purchase energy at lower rates (AASHTO 2021). The agency estimates that the amount of electricity generated by these highway right-of-way solar farms is enough to power 875 homes annually, translating into 2.3 tons of carbon dioxide saved each year (MassDOT 2021). The agency plans to expand the solar concept to parking facilities soon. Massachusetts is by no means the only state to explore this strategy; DOTs in Oregon, Ohio, and Colorado have led the way on using Right of Way (ROW) to install renewable energy sources.

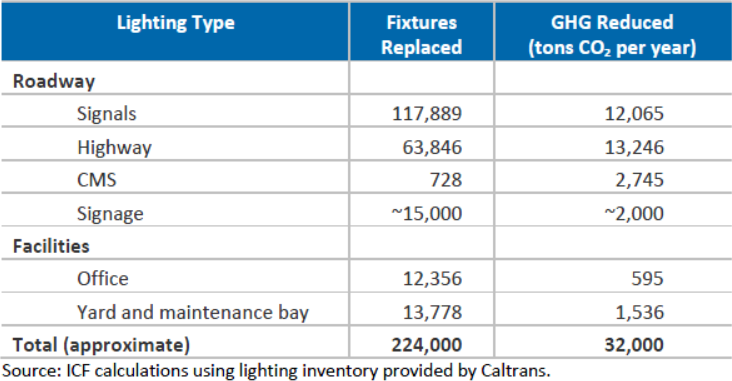

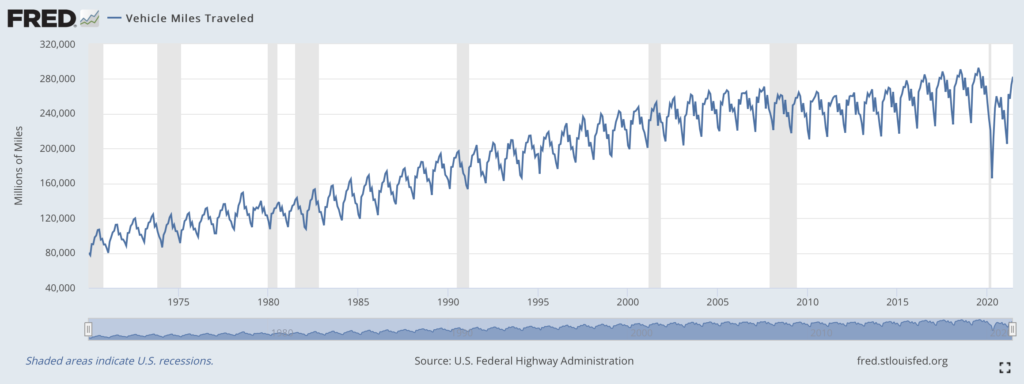

An itemized list of Caltrans roadway fixtures, and corresponding GHG reductions. Source: Caltrans Greenhouse Gas Emissions and Mitigation Report

The California Department of Transportation (Caltrans), through investments in clean energy generation over the past two decades, generates more electricity than the agency needs. This surplus can be attributed, in part, to longstanding participation in the federal Clean Renewable Energy Bonds (CREB) program, which has helped to finance the construction of over 70 solar facilities that collectively generate 2.38 megawatts (MW) of electricity, capable of powering over 500 homes annually. Caltrans has also been able to reduce its energy usage by converting lighting infrastructure to more efficient bulbs, changing the majority to LED. By replacing these fixtures, the agency has reduced the amount it would otherwise have emitted by 32,000 tons of carbon dioxide annually.

Electric Vehicles (EV)

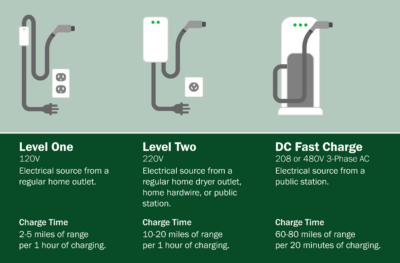

Fleet conversion is seen by state and federal lawmakers as a priority for achieving carbon emissions reductions. Many state transportation agencies are already planning for, and supporting, electric vehicle usage across their networks. From statewide fleet conversions, to fast charging networks, to using the tools of policy to incentivize the transition for consumers, state DOTS are adapting to take advantage of this new technology.

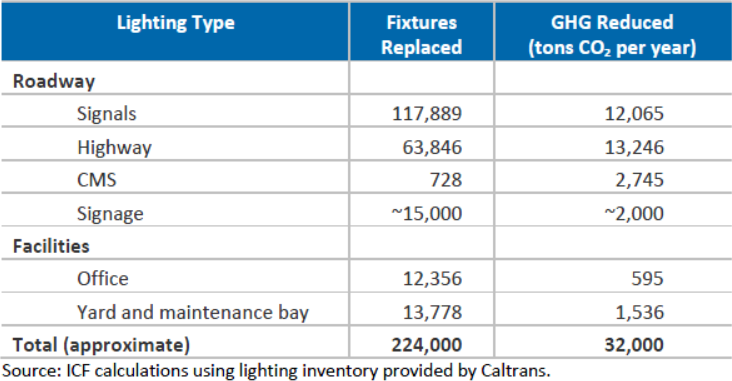

One aspect of NJ’s EV conversion plan is to develop a robust network of fast chargers, which is already underway. Source: NJDEP

In New Jersey, the New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection (NJDEP) and NJDOT are playing a pivotal role in the Statewide Energy Plan, which aims to reduce emissions to net zero by 2050. The rollout of EVs and related support infrastructure are integral to achieving this net zero emissions goal. This effort includes mapping out a statewide charging network and investing in the transition of the NJDOT fleet to all-electric vehicles, as other states are doing.

Some of New Jersey’s EV efforts, such as new charging infrastructure, are funded by Volkswagen settlement funds, which were disbursed to each of the fifty states. Colorado, for example, is using some of its share of the funds to convert the Colorado Department of Transportation’s (CDOT) fleet to more sustainable vehicles. To learn more about NJDOT and its partner agencies EV conversion work, see NJDOT Tech Transfer’s account of the state’s Energy Master Plan and use of Volkswagen funds, such as for the purchase of electric school buses.

Similar work is going on elsewhere. Colorado’s CDOT issued a Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) to convert 30 percent of all freight trucks in the state to zero-emission vehicles (ZEVs) by 2030. In California, a ruling by the state Air Resources Board (CARB) mandates that half of all freight vehicles sold in 2035 are to be zero-emission. In New Jersey, where emissions rules are enforced by the NJDEP, the agency proposed a rule directly modeled on the California model in 2021. This type of regulation uses a credit/deficit system to incentivize truck makers to sell ZEVs. Thus, under this phased system program, “the deficits incurred each year that must be offset by credits will begin in 2025, and increase every year through 2035, thereby increasing the total number of ZEV sales in the State.” (NJDEP 2021).

Through multiple mechanisms, state DOTs and partner agencies are working to convert both their own fleets, and those of users of the transportation systems they maintain. Here, too, there is room for innovation, for funding mechanisms, new policies, and technologies to support a wholesale EV transition.

VMT

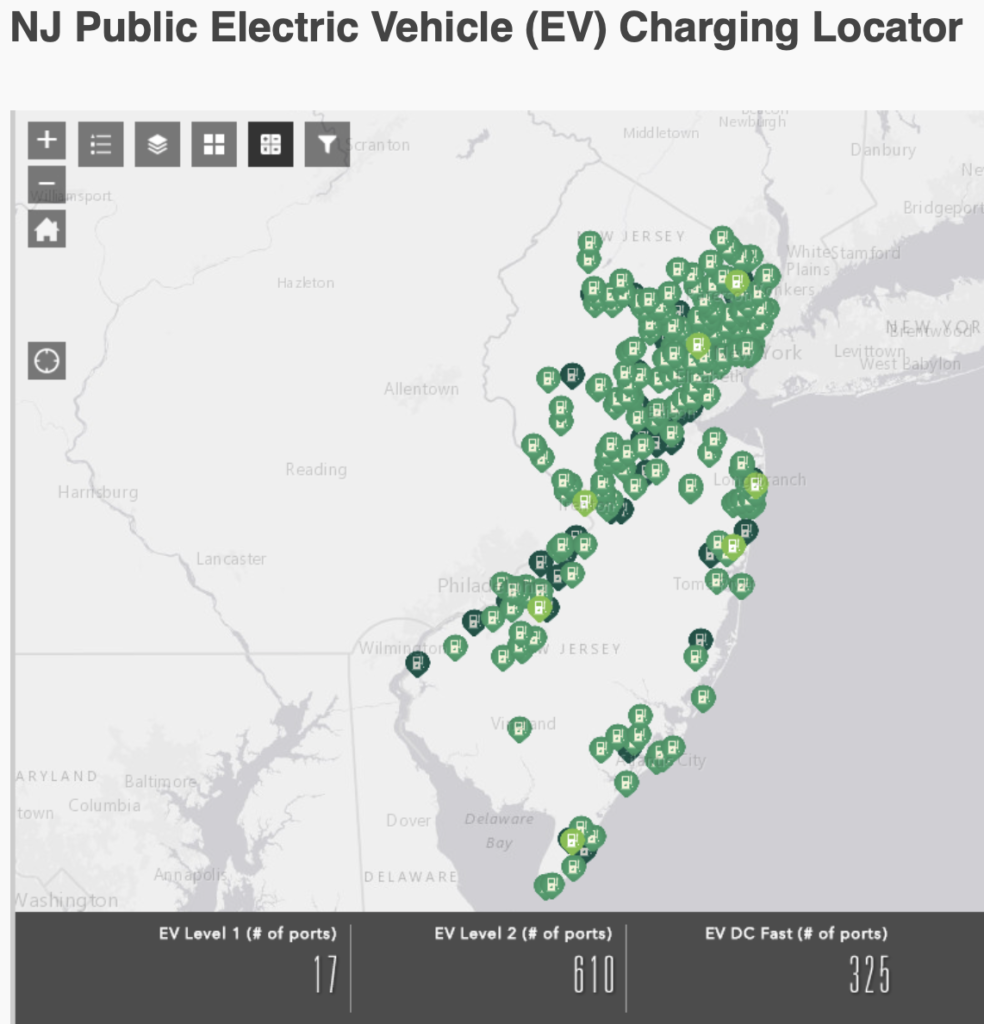

Vehicle Miles Traveled (VMT) refers to the total number of miles traveled along a roadway network. As VMT is reduced, so too are emissions, including both GHGs and harmful pollutants (such as nitrous oxide) that cause a myriad of health issues. Several VMT reduction strategies are being implemented by transportation and other agencies, including demand management pricing, land use planning, transit investments, and Work from Home (WFH) programs.

Annual Vehicle Miles Traveled (VMT) have been rising over the last five decades. Source: Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis

Using pricing strategies to manage roadway demand is increasingly being recognized as a means to alleviate traffic congestion. Using dynamic pricing, a managed “express” lane’s toll is priced based on demand, becoming more expensive as more motorists choose to use it. Depending on overall toll pricing levels, the strategy can induce price-sensitive users to change their time of travel, increase their vehicle-occupancy level, and/or change modal preference (e.g., switch to transit), potentially reducing the number of vehicle miles traveled.

Another pricing policy currently being explored is the Mileage Based User Fee (MBUF), in which drivers pay a per mile fee for roadway use, rather than funding roadway maintenance through the gas tax. This strategy is of particular interest since, as EV use increases, gas tax revenues will continue to fall, creating a deficit in the traditional funding structure for transportation. A flat MBUF, which would restore funding, can also serve to reduce total VMT by more directly conveying to drivers the cost of making a trip. The OReGO program, administered by the Oregon Department of Transportation is the only implemented example of this type of funding to date, though it is being studied in the Northeast. NJDOT Tech Transfer has written previously about ongoing research by the Eastern Transportation Coalition exploring the feasibility of implementing an MBUF program.

The promotion of land uses changes, such as transit-oriented development, is another proven way of reducing VMT. David Wilson | Wikimedia Commons

Several DOT climate plans promote more sustainable land uses along their networks as a means to achieve their goals. The Maryland Department of Transportation, for example, supports Transit-Oriented Development (TOD) in their Greenhouse Gas Reduction Act plan and predicts that the buildout of TOD in 20 zones across the state could remove 0.033 MMT of carbon dioxide by 2030. The Colorado Department of Transportation (CDOT), which mentions in its Transportation GHG Roadmap Briefing Update a multi-pronged strategy for reducing VMT, has hired a land use expert “to focus on partnering with local communities to more fully contemplate land use implications when designing infrastructure projects across the state.”

Related to land use planning is investment in multimodal transportation options. These strategies expand public transit, improve pedestrian safety, and support active transportation corridors, all efforts aimed to reduce VMT. For example, Caltrans released a detailed report on its Interstate 5 project in San Diego in which the agency states its plans to encourage a shift from single occupancy vehicle (SOV) trips to other modes by investing in expanded service on a parallel commuter rail route, and the construction of 23 miles of bicycle and pedestrian facilities along the same corridor. In New Jersey, NJDOT promotes smarter land use and expanded active transportation through the Transit Village Initiative, and the Transportation Alternatives Set-Aside program, which fund a variety of improvements and expansions of transit and active transportation infrastructure which may serve the purpose of lowering VMT by fostering more active, transit-connected communities. CDOT, through its Safer Main Street and Revitalizing Main Streets programs, makes similar investments to increase safety for all users and encourage alternate transportation modes.

Another method of reducing VMT is to invest in transit. CDOT has developed its “Bustang” service, offering intercity connections across the state on eight lines. The Florida Department of Transportation (FDOT) is piloting an approach in the St. Petersburg area, where buses on I-275 are permitted to drive on the shoulder under certain conditions. If the flow of traffic falls below 35 mph along the route, the bus may bypass the congestion by using the shoulder. FDOT also installed special red signals on on-ramps along this stretch of road to prevent collisions from merging vehicles. The Rhode Island Department of Transportation (RIDOT) piloted “Little Roady,” an autonomous electric shuttle service that circulated through Providence along a congested roadway. RIDOT’s 2020 Transit Forward RI Master Plan 2040 recommends further study of such services, as well as investing in transit connections to further curb vehicle usage.

Finally, as was demonstrated during the COVID-19 pandemic, a viable solution to bring down emissions is to reduce total VMT (see chart above). Moving forward, CDOT is looking to promote working from home — on a two or three day a week basis — as a climate strategy and department-wide practice. In 2021, the agency awarded $213,000 in telework grants through its CanDo Telework Grant program to local governments and non-profits to support remote work.

There is still much research and experimentation in the pilot testing, evaluation and deployment of innovation practices in materials, energy, fleet transition, and VMT reduction to meet overall GHG targets. Transportation agencies and the transportation workforce are being called upon to confront an extraordinary and perhaps existential challenge that will require an ongoing commitment to advancing innovations in policies, processes, and procedures.

Ongoing Research

The National Cooperative Highway Research Program (NCHRP), a research program led by the Transportation Research Board (TRB), funded by AASHTO member states and the Federal Highway Administration (FHWA), works to develop implementable research addressing critical issues in the transportation sector. This collaborative initiative recently published Incorporating the Costs and Benefits of Adaptation Measures in Preparation for Extreme Weather Events and Climate Change as a guide for incorporating the Cost Benefit Analysis (CBA) process for adaptation planning and asset management. While resilience research and resources will be more thoroughly covered in the second part of this series, the TRB’s Resilience Research page provides an excellent overview for resilience planning.

Several upcoming NCHRP research projects will further inform planning for the GHG reduction process for transportation agencies. Research for the forthcoming Methods for State DOTs to Reduce Greenhouse Gas Emissions from the Transportation Sector was completed in March 2021, and investigative work for Assessment of Regulatory Air Pollution Dispersion Models to Quantify the Impacts of Transportation Sector Emissions was completed in June 2021. Another study, Considering Greenhouse Gas Emissions and Climate Change in Environmental Reviews: Resources for State DOTs, was awarded in July 2021, with research expected to conclude by October 2023. Succinct summaries of current and upcoming research, sorted by topic can be viewed on TRB’s Research Snap Searches page.

Conclusion

Over the past century, the predominant impetus for transportation has been that of expansion and maintenance of the nation’s Federal, state and local roadway networks. However, as suggested by the initiatives underway by the many state DOTs highlighted in this literature scan, the role of the state DOT is changing. As has been shown, the state transportation agency, with its vast resources and footprint, has many avenues by which it can promote necessary innovations to help reduce GHG emissions, and so limit the impending threat of climate change.

The necessity of reducing Greenhouse Gas Emissions, Vehicle Miles Traveled, and building resilient infrastructure that can withstand increasingly severe weather requires innovations in both process and technology in the transportation sector.

There is, of course, work to be done beyond GHG reduction. The second installment on this theme will cover how state DOTs are currently rising to the challenge of resilience, innovating through planning, engineering, and research, to strategically strengthen our transportation infrastructure to weather a more intense, and unpredictable, climate.

Resources

AASHTO Center for Environmental Excellence. (2021). MassDOT Public-Private Partnership Generates Solar Energy on Highway Rights of Way. American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials. https://environment.transportation.org/case_study/massdot-public-private-partnership-generates-solar-energy-on-highway-rights-of-way/

Azari Jafari, H., Gregory, J., and Kirchain, R. (2020). Potential Contribution of Deflection-Induced Fuel Consumption to U.S. Greenhouse Gas Emissions. Transportation Research Record. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1177/0361198120926169

California State Transportation Agency. (2021). Climate Action Plan for Transportation Infrastructure. California State Transportation Agency. https://calsta.ca.gov/-/media/calsta-media/documents/capti-2021-calsta.pdf

Caltrans. (2021). Caltrans Greenhouse Gas Emissions and Mitigation Report. Caltrans. https://dot.ca.gov/-/media/dot-media/programs/transportation-planning/documents/office-of-smart-mobility-and-climate-change/ghg-emissions-and-mitigation-report-final-august-2-2020-revision9-9-2020-a11y.pdf

Caltrans. (2016). I-5 North Coast Corridor Public Works Plan/Transportation and Resource Enhancement Program. Caltrans. https://dot.ca.gov/caltrans-near-me/district-11/programs/district-11-environmental/i-5pwp-toc/s5-1

Colorado Department of Transportation Multimodal Planning Branch. (2021, July). Transportation GHG Roadmap Briefing Update. Colorado Department of Transportation. https://www.codot.gov/programs/environmental/greenhouse-gas/ghg-briefing-memo-july-2021.pdf

Environmental Protection Agency. (2019). Sources of Greenhouse Gas Emissions. https://www.epa.gov/ghgemissions/sources-greenhouse-gas-emissions

Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Global Warming of 1.5° C. https://www.ipcc.ch/sr15/

Maryland Department of Transportation. (2020). Greenhouse Gas Reduction Act. https://www.mdot.maryland.gov/OPCP/MDOT_GGRA_Plan.pdf

Massachusetts Department of Transportation. (2021). MassDOT Renewable Energy Projects. https://www.mass.gov/info-details/massdot-renewable-energy-projects

National Cooperative Highway Research Program. (2021). Incorporating the Costs and Benefits of Adaptation Measures in Preparation for Extreme Weather Events and Climate Change—Guidebook. Transportation Research Board. https://www.nap.edu/catalog/25744/incorporating-the-costs-and-benefits-of-adaptation-measures-in-preparation-for-extreme-weather-events-and-climate-change-guidebook

National Cooperative Highway Research Program. (2021). Methods for State DOTs to Reduce Greenhouse Gas Emissions from the Transportation Sector. Transportation Research Board. https://apps.trb.org/cmsfeed/TRBNetProjectDisplay.asp?ProjectID=4384

Oregon Department of Transportation. (2021). Climate Actions Under Consideration. https://www.oregon.gov/odot/Programs/Documents/Climate%20Office/Climate_Actions_Under_Consideration-ODOT_5-Year_Climate_Action_Plan.pdf

Oregon Department of Transportation. (2021). ODOT Climate Action Plan. https://www.oregon.gov/odot/Programs/Documents/Climate%20Office/Climate_Action_Plan_Overview.pdf

Oregon Department of Transportation. OReGO. https://www.myorego.org/

Rhode Island Division of Statewide Planning. (2020). Transit Forward RI 2040. https://transitforwardri.com/pdf/TFRI%20Recs%20Briefing%20Book-Final%20201230.pdf

Sachs, S. (2021). Pinellas Buses to Drive on I-275 Shoulder in New FDOT Pilot Program Set to Start in June. News Channel 8. https://www.wfla.com/news/pinellas-county/pinellas-buses-shouldering-onto-interstate-in-new-fdot-pilot-program-set-to-start-in-june/

State of New Mexico. (2019). New Mexico Climate Strategy. https://www.climateaction.state.nm.us/documents/reports/NMClimateChange_2019.pdf

State of Rhode Island. (2020). Clean Transportation and Mobility Innovation Report. http://climatechange.ri.gov/documents/mwg-clean-trans-innovation-report.pdf

Transportation Research Board. (2021). TRB Snap Searches. http://www.trb.org/InformationServices/Snap.aspx

Transit Cooperative Research Program. (2021). An Update on Public Transportation’s Impacts on Greenhouse Gas Emissions. Transportation Research Board. https://www.nap.edu/download/26103