Mar 3, 2022 | Innovation Spotlight, Innovative Initiative, News

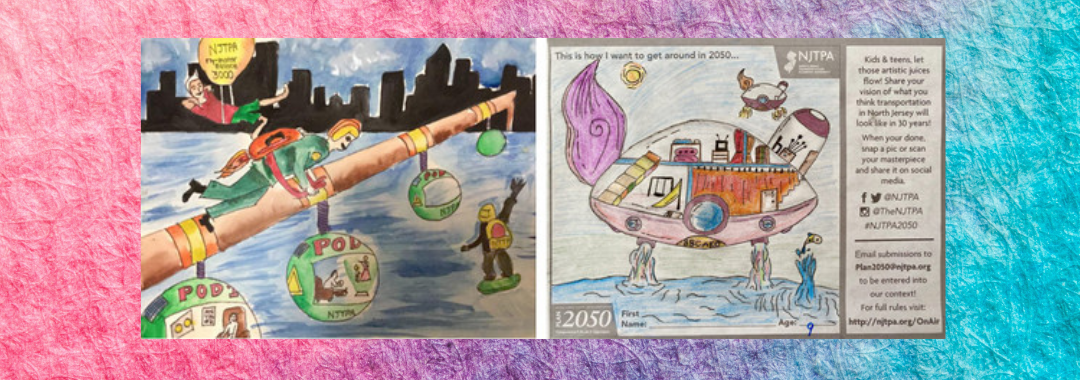

FHWA promotes virtual public involvement and innovative public engagement strategies through its Every Day Counts (EDC-6) innovations. The FHWA’s EDC Newsletter of March 3, 2022 featured the North Jersey Transportation Planning Authority’s creative efforts...

Nov 15, 2021 | Innovative Initiative, Online Learning

Early, effective, and continuous public involvement brings diverse viewpoints and values into the decision-making process. Transportation agencies can increase meaningful public involvement in planning and project development by integrating virtual tools into their...

Sep 13, 2021 | Innovation Interview, Innovation Spotlight, News

Virtual Public Involvement presents an opportunity to expand the community engagement process. An FHWA Every Day Counts Round 6 initiative (EDC-6), Virtual Public Involvement (VPI) gives participants an opportunity to engage, other than through a traditional, physical...

Apr 8, 2020 | News, NJ STIC

FHWA promotes virtual public involvement and other innovative public involvement tools through its Every Day Counts-5 innovations. FHWA notes several benefits of a robust public involvement process that employs technology to bring public involvement opportunities to...